DIY Atomic Clock

Table of Contents

Introduction: I Lied#

Technically speaking, it’s not an atomic clock. Because there’s no caesium or rubidium oscillator keeping the clock disciplined.

But I did make a GPS disciplined stratum 1 time server. It gets its time from GPS satellites — each carrying onboard atomic clocks — and makes that accurate time available to devices on my network.

So close enough…

This post will go over what an atomic clock actually is, the different terminologies associated with electronic timekeeping and how you can build your own GPS clock with some spare parts.

Click here if you want to skip straight to my setup and how you can duplicate it.

Why Is Accurate Time Important?#

Accurate time and precision timekeeping is vital for everyday life. Whenever you make a financial transaction, securely log into a website, attempt a GPS fix or trade stocks – that requires a precise and accurate date stamp to complete. Without accurate time our lives would be a mess.

Personally, I’m just particularly fond of precision and accuracy — and timekeeping is a field that especially fascinates me.

What Actually Is an Atomic Clock?#

Before diving into how I built mine, let’s talk about what “atomic” really means in this context.

For the longest time I believed that atomic clocks were considered so accurate because they would somehow determine the age of something and give us the current date and time. I was wrong.

Did you know: the current time is actually kept by taking a weighted average from around 450 atomic clocks around the world, a project named TAI (abbreviated from the french: temps atomique international, meaning International Atomic Time).

Hypothetically, if something were to reset all the clocks (on earth and in space), we would have absolutely no way of restoring the time, and would have to start over.

What makes an atomic clock special, is that it uses the resonant frequency of atoms (e.g., caesium-133, rubidium-87) to maintain an accurate pulse, not find out the time. Their superpower is battling against drift.

The basic explanation to how they work is, they monitor the resonant frequency of atoms. So much like how we can get a stable frequency from a quartz crystal by applying a voltage to it, we can do something similar with caesium, hydrogen and rubidium atoms.

A more in-depth explanation would be: for example, in a caesium atomic clock, microwaves are tuned to the natural resonant frequency of caesium-133 atoms. When the frequency is exactly right, maximum energy absorption occurs — that frequency defines one second. A feedback loop continuously adjusts the oscillator to stay locked on that frequency.

Congrats, you now know how an atomic clock works.

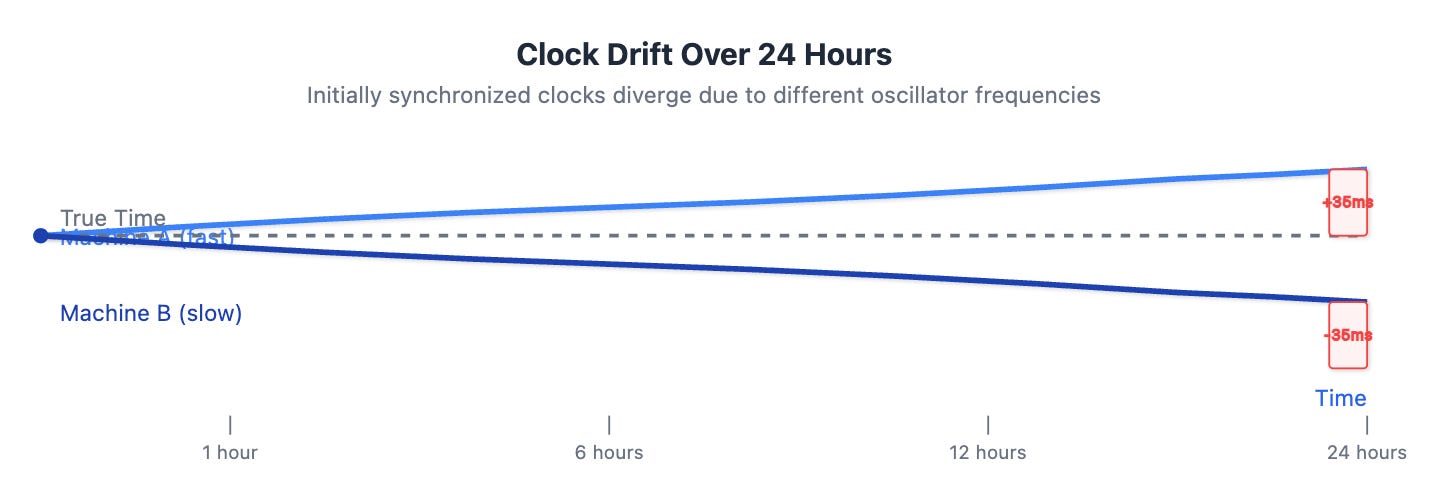

Understanding Drift#

Drift is a measure of how much clocks deviate from the set time, over time. All clocks drift, you set your time but after a month or so you’re off by a couple seconds, after a year you’re off by a few minutes, etc.

Mechanical Movements#

A mechanical movement (e.g., a Swiss watch) is a non-electrical timekeeping device, it’s powered by the mainspring – which is like a battery in this context, but instead of chemical energy it is powered by stored kinetic energy. The drift of mechanical movement depends on several factors:

- Gravity

- Magnetism

- Quality of the movement

- Temperature Changes

And usually their drift is around ±10 to ±30 seconds/day, which is obviously quite poor compared to quartz movements.

Quartz Movements#

Quartz movements are battery powered electric timekeeping devices, they’re inexpensive and ubiquitous. The device you’re reading this on is using a quartz oscillator(s). These use the piezoelectric effect of a quartz crystal to generate a stable frequency when a voltage is applied, this frequency is tuned by cutting the crystal in a certain way and then used to provide a reference for a second. These are quite accurate, but still drift. The following external factors affect the drift of quartz oscillators:

- Magnetism

- Physical Shock

- Temperature Changes

- Voltage Fluctuations

And usually their drift is around ±15 seconds/month, which is incredible compared to mechanical movements. Great for everyday timekeeping and general-purpose use cases. But when it’s mission critical to have very precise time, atomic clocks are where it’s at.

Atomic Clocks#

As I mentioned earlier, atomic clocks are simply disciplined by the resonant frequency of certain atoms, instead of something like a mechanical or quartz oscillator. And they are orders of magnitude more accurate than the previous examples, however they do still drift – and they are still affected by elemental factors, such as:

- Gravity

- Magnetism

- Temperature Changes

But here’s the reason they are favoured in industrial applications (e.g., scientific sector, financial sector, etc.). If we look at caesium clocks, they only lose about a second every 30 million years. That’s a ridiculous leap in accuracy from mechanical and quartz movements.

What Is a “Stratum”?#

A stratum is broadly defined as “a layer of something”. In geology it’s a distinct layer of rock, and in sociology it refers to a level or class to which people are assigned according to their social status, education or income.

In the context of timekeeping, however, we refer to different “layers” of clocks as stratum.

| Stratum | Function | Example |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | Actual hardware time sources | Atomic clocks, GPS clocks. |

| 1 | Networked time servers directly connected to stratum 0 sources | A Raspberry Pi with a GPS dongle (like mine), a data centre time server with a rubidium oscillator. |

| 2 | A time server that relays a stratum 1 for availability/security | A server that takes in time from stratum 1 and serves it to the public or a few more computers |

NTP defines strata from 0 (reference source) through 15 (lowest valid layer); stratum 16 is considered unsynchronised.

So these stratum not only define the hierarchy or time servers, it also directly represents their priority level.

My Clock/Time Server#

So, as I said before, it’s not technically an atomic clock. It only relays the atomic time from GPS/GLONASS satellites that have onboard rubidium clocks.

The Pi polls the satellites and disciplines its own clock using GPS, the built-in quartz oscillator keeps the time steady until the next update from the satellites.

Unfortunately it’s not even that accurate because it’s just using NMEA messages to get the time. If my dongle was capable of PPS I would be able to get a more precise clock, but I just built this over a weekend using spare parts so…

Ideally, I’d use a second-hand rubidium oscillator that outputs PPS and a 10mhz signal, which would keep the Pi’s clock at an atomic level of accuracy, give it a UPS (uninterruptible power supply), and an addon RTC (real-time clock) – but that’s way out of my budget sadly.

One day…

However, the current setup is more than good enough for my purposes. It’s a fun, interesting little project that can be done for cheap.

Parts I Used#

- Raspberry Pi 3 Model B+

- Generic GPS Dongle (Powered by a u-blox 7 chipset)

That’s literally all it takes.

How It’s Setup#

I literally just installed a fresh copy of Raspbian Lite, plugged in my GPS dongle, installed a few packages, wrote a few config files, and we’re off to the races.

It sits on the windowsill of my student accommodation, so it can maintain a reliable GPS fix.

On boot the Pi will wait until it’s connected to the internet, then poll a public NTP pool (time.cloudflare.com) because I don’t have an RTC so whenever the Pi cold boots it defaults to the time the MicroSD card was imaged. It then waits for a GPS fix, advertising itself as Stratum 10 (low priority). Once it gets a fix it adjusts its own time to what is received from GPS and advertises itself as Stratum 1.

I also created a little web-app, a clone of time.is, that runs on the Pi and spits out its time. Mainly so I could attempt to set my Casio F-91W but also it’s also just cool.

Here it is in action:

Why Did I Build It?#

I was losing my mind over coursework and wanted to actually make something. There’s this guy online called Jeff Geerling, I’ve been watching his content for a while and I love his work. I recalled he made a few videos on atomic clocks and went over setting up a Raspberry Pi Grandmaster Clock, and thought it’d be fun to recreate that with the spare parts I had on hand.

I’ve also been plagued with the problem of desynchronised time on a few of my servers, causing issues with logging and one-time passcodes. And at the time I just fixed it by enabling NTP sync using public NTP pools (I don’t know why I didn’t do that in the first place, shameful oversight on my behalf as a sysadmin) and it piqued my curiosity, the potential of self-hosting my own time server.

The goal was less to have the perfect accurate time (otherwise I’d be forking out hundreds of pounds for a rubidium oscillator), and more to have a consistent synchronised time across my devices.

And I’m very glad I finally did, It’s been a fascinating project, and I’ve learned a lot from it. It’s funny how much of Computer Science is tied in from Physics, Chemistry, etc.

How to Make Your Own GPS Disciplined Time Server#

Parts Needed#

- Spare computer (e.g., old laptop, Raspberry Pi (or similar SBC), anything that can access your network, has USB ports and can run Linux)

- USB GPS Dongle (any of the following or similar will do):

Instructions#

Connect everything.

Flash a MicroSD Card/Install the OS of your choice (for this short guide I’m assuming Debian is used, if you’re using a different distro I imagine you know what you’re doing).

Install

chronyandgpsd:sudo apt update; sudo apt install chrony gpsdConfigure

gpsd:sudo vim /etc/default/gpsd# /etc/default/gpsd START_DAEMON="true" GPSD_OPTIONS="-n" DEVICES="/dev/ttyACM0" # Replace this with your device, usually under /dev/ttyACM0 though USBAUTO="true" GPSD_SOCKET="/var/run/gpsd.sock"Configure

chrony:sudo vim /etc/chrony/chrony.conf# /etc/chrony/chrony.conf # --- Reference clock (GPS NMEA via gpsd SHM0) --- refclock SHM 0 refid GPS precision 1e-1 offset 0.9999 delay 0.2 prefer # --- Optional fallback NTP servers (for startup or GPS loss) --- # pool time.cloudflare.com iburst maxsources 1 maxdelay 0.4 # Uncomment this to use a public NTP server when GPS is unavailable # --- Core chrony settings --- driftfile /var/lib/chrony/drift leapsectz right/UTC makestep 0.1 -1 # rtcsync # Uncomment this if you have an RTC # --- Local stratum fallback (only if GPS lost) --- local stratum 10 orphan # --- Allow clients on your LAN --- allow 10.0.1.0/24 # Replace with your subnet to serve NTPEnable the services:

sudo systemctl enable --now chrony gpsdPoint your other devices’ NTP server configurations toward the FQDN or IP address of your time server.

Enjoy.

You can monitor

chronyandgpsdusing the following commands:

cgps: Shows you the information being pulled from your GPS module, this is where you can check if you have a fix or notsudo chronyc sources: Shows you your sources, if all is well it should show your GPS dongle as a time sourcesudo chronyc tracking: Shows you the status of your NTP server

Conclusion#

This project might not be a “real” atomic clock, but it taught me a ton about how modern timekeeping works — and how easy it is to build something surprisingly precise with off-the-shelf parts.

If you’ve ever wanted to get into NTP, GPS, or even just understand why your phone’s clock never drifts, try making your own stratum 1 server. It’s cheap, educational, and deeply satisfying to watch your little Raspberry Pi become part of the world’s timekeeping infrastructure.